One might not think Martin Scorsese would be the right person to direct a movie like Killers of the Flower Moon. Scorsese grew up in what was once called “Hell’s Kitchen.” People are trying to change that phrase and refer to it as Clinton as it’s always been. But it’s a neighborhood, a region of the Big Apple that had mostly white people both of Irish and Italian ancestry as well as Latino/Hispanic. And it was often considered to be one of the worst places in New York City to live because of crime and atmosphere.

Oklahoma has always been like NYC in how people from the other part of the world have a different view on it. Scorsese loves NYC. So does Robert DeNiro, who despite his name is mostly Irish. Things have changed over time. But 100 years ago, the mobsters battled for power during Prohibition and anybody could be killed over anything, especially money and wealth. And just like Bill the Butcher and his Natives in Gangs of New York, all immigrants were being discriminated against, even Irish and Italians.

So, both Scorsese and DeNiro were born into a world where white people didn’t like their own kind just because of different ancestry. The bigotry and prejudices they must have seen in their own neighborhoods can be reflected in Flower Moon, a brutally violent and disturbing point in American history that people wanted to forget because it didn’t sit well in the history books.

Crude oil had been underground for centuries before the advent of automobiles and gas-powered engines made it a huge commodity. There was just one problem. The land where they found it in Oklahoma was considered the Osage Reservation and it made the Indigenous Native Americans rich and wealthy, much to the chagrin of the white people who had settled in the state or moved to be roughnecks on the oil rigs. Why should white people work to make the “Injuns” rich?

Of course, the 20th Century meant they couldn’t rely on the U.S. military to massacre Native Americans like they did in the 19th Century. They had a more sadistic and effective way to make sure the white people got the rights to the oil. They would marry into the families and then kill them or have them killed. But this wasn’t done in secret. The white people knew they could do this and get away with it, because as one Osage says they’d get in more trouble kicking a dog than killing an Osage.

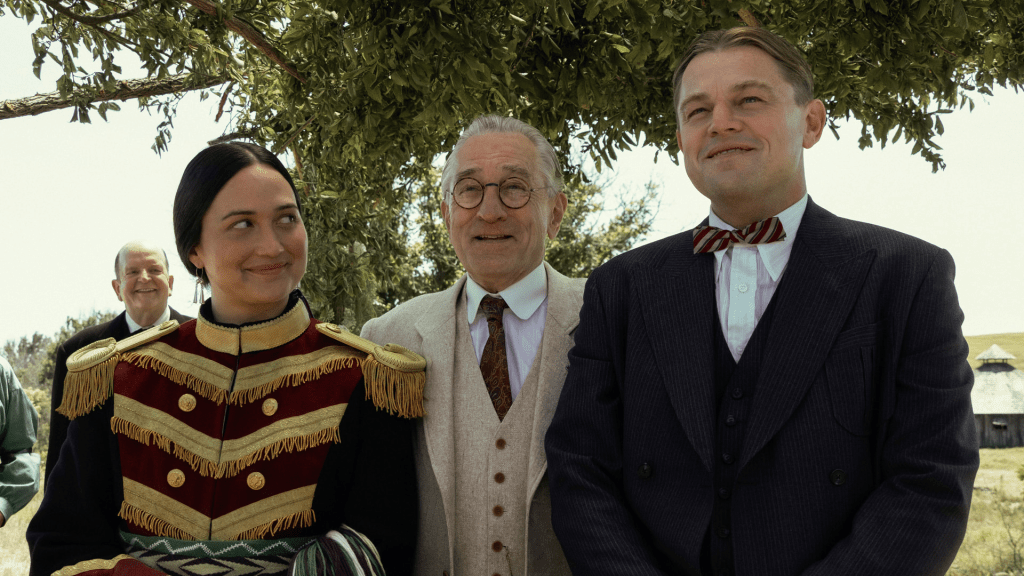

During one hard to watch scene, Scorsese films just how little the white people felt of the dead Osage as an autopsy occurs at the scene where a body is found while Mollie Burkhardt (Lily Gladstone) watches in horror and sadness as her husband, Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio) tries to comfort her as it’s likely he’s somehow involved with the murder. Later in a flashback, we see how a white man nonchalantly kills this person. Most of them were willing to kill the Osage who they had known for years if not their whole life, even if they were they’re own children.

Ernest’s uncle, William King Hale (DeNiro in a true villainous role) is a powerful man, who argues that basically we’re all going to die some day so what’s the big deal as long as they get rich. He even arranges for one of his workers, an Osage, to be killed so he can collect the insurance. One thing that’s not mentioned in the movie but was mentioned in David Grann’s non-fiction book of the same name was how there was a smear campaign of the Osage to portray them as gluttonous greedy people, the way we’d see trust-fund babies today.

But Scorsese who co-wrote the screenplay with Eric Roth shows just how people abused them for their money. Photographers haggle with Osage over the photographs that cost about $45-50 which are outrageous for that time. A car salesman pleads shamelessly mentioning his family’s health for an Osage family to purchase a vehicle. And even still, they had white people in charge of their money even questioning how much they could have at one time. Character actor Gene Jones plays a character who despises Osage and Native American and talks down to them, but he’s in charge of the money for Mollie and her family.

This might be one of the most despicable characters DiCaprio has played, even worse than Calvin Candie in Django Unchained. At least in that movie, he had some love, admiration and respect for some black people, namely Stephen, his house servant played by Samuel L. Jackson. Here Ernest appears to be the type of person who despises Native Americans and wants to use them for what he can get out of it. He’s shown robbing them and even allowing the desecration of the grave of Mollie’s sister so they can snatch her jewelry. He even casually greets a Klan member as the Ku Klux Klan march in a town parade. Originally, DiCaprio was considering playing the federal agent Thomas Bruce White Sr. who investigated the murders. Doing so would have made Flower Moon a “white savior” movie, which Scorsese said he wanted to change after meeting and working with the Osage Nation.

It’s a wonderful change. I, and other people I talked to, were concerned about this as well. White is played by Jesse Plemons who doesn’t appear until two hours into the three-and-a-half hour movie. It’s the right time. This isn’t really about law enforcement investigating murders against people. That was the basis of Grann’s book which led to the formation of the FBI. It’s about how the Osage people were neglected. It was only after the Osage traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet and speak with President Calvin Coolidge, which Mollie pleads for help. The Osage also donated $25,000 to assist in the investigation.

By changing this approach, Scorsese and Roth have made Mollie the central figure of the movie. And while she spends much of the middle part sick in bed, as it is implied Ernest is slowly poisoning her as she suffers from diabetes and needs insulin shots, Gladstone gives a wonderful performance from beginning to end. This is her movie. The way she acts around Ernest when they first meets indicates she knows what he’s up to but she might have some fun with it anyway. As she tells her relatives, she knows he’s after her money.

But as they eventually get married and start raising a family, it becomes apparent, she is in love with Ernest. However, he may or may not be totally in love with her. It’s obvious he cares and loves his children. Yet at the same time, Ernest isn’t the brightest person and Hale is the one calling the shots. During a scene that got a lot of publicity before it was released, Hale violently paddles Ernest at a Masonic lodge when one of his petty crime capers backfires. Hale is smart. Ernest isn’t. And because their victims were people local law enforcement didn’t care about, they got away with it so long.

It’s even implied while Hale is watching a news reel in a theater that he may have had something to do directly or indirectly with the Tulsa Race Massacre. However, Scorsese and his long-time editor/collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker keep the pace running smoothly showing us just what we need to see. When the final hour or so looks like it’s going to turn into a legal drama as John Lithgow appears as prosecutor Peter Leaward and Brendan Fraser as attorney W.S. Hamilton, it’s really just to show how much of a control Hale has. People have criticized Fraser’s performance but litigators are showmen. They know how to command the courtroom, even from the judge.

This is really about levels of loyalty, love and where do you draw the line on betrayal. It’s similar to a lot of Scorsese’s most popular and beloved movies, such as Goodfellas, The Departed and Casino. He’s called this his first western, but I think that distinction goes to Casino. Oklahoma had only been a state for a couple decades during this movie’s timeframe and the lawlessness wasn’t the ragamuffins Hale hired to do his dirty work but people like Hale himself. The cattle barons of the late 19th Century became oil barons in the 20th Century.

You can see similarities of Paul Thomas Anderson’s iconic There Will Be Blood and I’m sure Hale and Daniel Day-Lewis’ ruthless Daniel Plainview would’ve been squaring off against each other if they existed in the same universe. And just like that movie, Rodrigo Prieto as director of photography captures the beauty of the Great Plains in the early 20th Century. Robbie Robertson’s musical score adds to the drama. Robertson died two months before the movie opened and it’s likely he’ll win the Oscar.

The movie also reminds me of Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, quite possibly his best work ever. (Please don’t fight me on this.) Just like he did in that movie, he shows he may be one of the best movie storytellers working now and of all time. Production was halted due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which allowed them to negotiate a co-distribution deal between Paramount Pictures and Apple Original Films. While it cost $200 million but didn’t even break even, not all movies have to be huge blockbusters.

This is a story that’s more important than Barbie or even Oppenheimer (which will be the biggest contender at the Oscars). Like Barbie herself, Mollie and other Native American women fought the patriarchy and continue to fight it this day. Some people have questioned the movie’s ending which switches to an old-timey radio production in a theater as white actors re-enact the story to a white audience. This occurred during their life time and they likely didn’t know about it. It ends with Scorsese appearing as an actor reading Mollie’s obit. I think it’s him telling other filmmakers that they need to start telling better stories.

And then we end with the Osage chanting and beating on a drum showing their spirit will continue and can’t be broken.

What do you think? Please comment.